Why Do Doctors Need Trauma-Informed Care?

This may seem like an unusual topic—after all, isn’t trauma-informed care something doctors provide to their patients? However, trauma is increasingly recognised as not just what happens to someone, but how their mind and body respond to those events.

The Overlooked Impact of Trauma in Medical Training

At Whole Hearted Medicine, we believe that trauma in medical training is often underestimated. From the intense competition to enter medical school, the constant relocations for training positions and the gruelling demands of specialty exams with no guarantee of a job at the end thanks to significant training bottle necks and poor workforce planning, many aspects of medical education can lead to chronic stress and burnout in doctors.

A systematic review by Alves et al. (2023)1 found that social support is one of the most significant protective factors against burnout. Yet, many doctors cite strained personal relationships as one of the biggest sacrifices made during training. Without strong support networks, the emotional toll of medical training can be profound.

How Medical Education Can Be Traumatic

Although the “see one, do one, teach one” approach is fading, many doctors have experienced this sink-or-swim culture of medical education. Research shows that medical students often start with better-than-average mental health, but their well-being declines significantly within the first two years of study (Voltmer et al., 20212). From the ever present fear of making a mistake to the immense workload demands on junior doctors and trainees that often call for them to forsake their own basic physiological needs in favour of continuing to work- doctors perform their roles under huge stress and often with little immediate support.

The Impact of Stress on Doctors

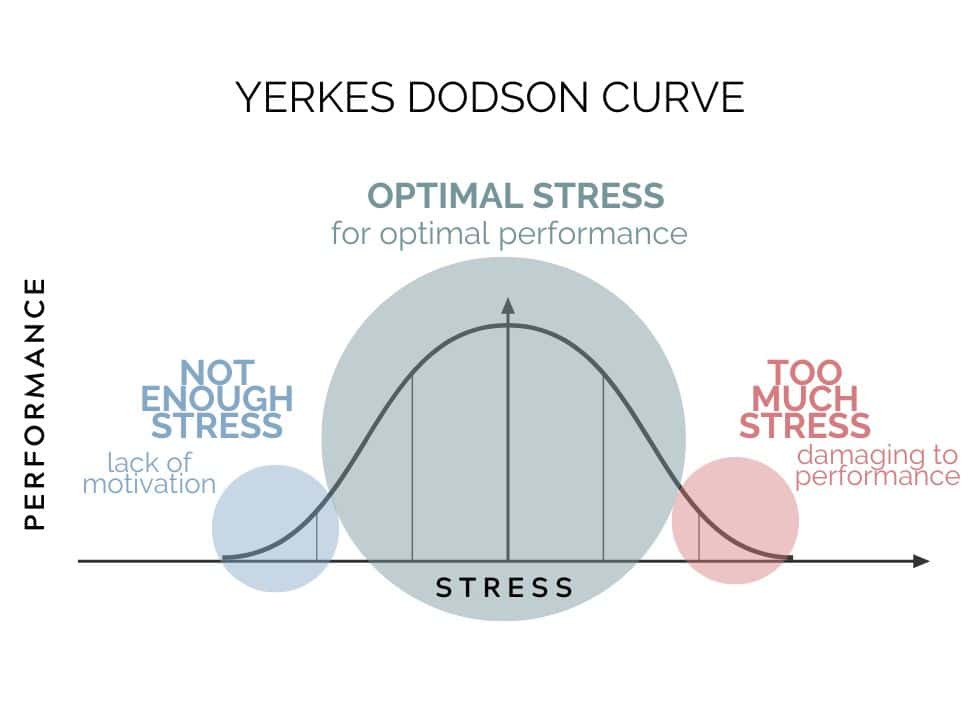

The Yerkes-Dodson Stress-Performance Curve demonstrates that while a moderate amount of stress can enhance performance, excessive stress reduces cognitive function. Morava et al. (2024)3 found that acute stress in university students led to increased mind wandering and lower comprehension—a significant concern for doctors required to process large amounts of critical information. Furthermore, a 2021 paper by Arnsten & Shanafelt4 outlined the neurobiological consequences of poorly managed chronic stress in clinicians on the pre-frontal cortex, resulting in “… (impaired) cognitive functions, which can result in diminished working memory and attention regulation, poor decision-making and other cognitive deficits…”. The cumulative effect of many acutely stressful daily interactions, minimal support or time for professional reflection and complicating factors such as fatigue, lack of autonomy and high levels of burnout within the profession means that doctors are particularly susceptible to the effects of chronic stress- both on performance and wellbeing.

Mental Health in Medicine: Breaking the Stigma

According to the National Mental Health Survey of Doctors and Medical Students (Beyond Blue, 2013)5, doctors experience higher levels of psychological distress and suicidal thoughts compared to both the general population and other professionals. The fear of stigma and potential career repercussions often prevents doctors from seeking help.

From microaggressions to bullying and structural biases, the medical culture can sometimes perpetuate trauma rather than alleviate it. Creating an environment where doctors feel safe to seek support is essential for addressing this growing concern.

The Role of Self-Compassion in Doctor Well-Being

One of the core principles of self-compassion, as defined by Dr. Kristin Neff (2023)6, is the concept of common humanity—recognising that suffering is a shared human experience rather than something to be endured in isolation.

At our Whole Hearted Medicine retreats, we witness this firsthand. When doctors connect and share their struggles, they realise they are not alone in their experiences. As one participant shared:

“I could see that nearly all the attendees were struggling. Some were extremely distressed, but everyone was very respectful and supportive. The atmosphere was one of support for each other as human beings.”

Applying Trauma-Informed Care in Medical Education

In our retreats, we incorporate the five key principles of trauma-informed care that we feel should be present in all areas of medical education and support:

- Safety: Ensuring physical and emotional safety through confidentiality and compassion.

- Choice: Respecting learner autonomy and providing clear communication about expectations, outcomes and support available.

- Collaboration: Creating learning spaces that value discussion and exploration of sometimes ethically difficult concepts, providing opportunities in teaching sessions for group work and sharing.

- Trustworthiness: Addressing potential interpersonal factors including communication issues that may impact upon task clarity, placing & upholding clear boundaries and understanding the role that our own personal triggers may have in our interactions with others.

- Empowerment: Co-creating learning experiences that validate individual experiences.

A Holistic Approach to Doctor Well-Being

Bringing a trauma-informed lens to the care & education of doctors and medical students isn’t about labelling all doctors and medical students as suffering from post traumatic distress. Instead, it aligns with adult learning principles—which prioritise learner autonomy, readiness, and a collaborative teaching environment, ensuring that the mental health of those who have or are experiencing post-traumatic distress is not made worse by accessing that care or educational opportunity.

As a participant from our retreats reflected:

“I feel like I have a better understanding of self-compassion and why I need it in my life. I also learned that I am not alone in my feelings. I’ve learned to be kinder to myself and more accepting of my flaws.”

At Whole Hearted Medicine, we are committed to providing trauma-informed medical education—ensuring doctors and medical students receive the support they need while fostering a healthier profession for future generations.

- Alves, L., Abreo, L., Petkari, E., & Pinto da Costa, M. (2023). Psychosocial risk and protective factors associated with burnout in police officers: A systematic review. Journal of affective disorders, 332, 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.03.081 ↩︎

- Voltmer, E., Köslich-Strumann, S., Voltmer, J. B., & Kötter, T. (2021). Stress and behavior patterns throughout medical education – a six year longitudinal study. BMC medical education, 21(1), 454. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02862-x ↩︎

- Morava, A., Shirzad, A., Van Riesen, J., Elshawish, N., Ahn, J., & Prapavessis, H. (2024). Acute stress negatively impacts on-task behavior and lecture comprehension. PloS one, 19(2), e0297711. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297711 ↩︎

- Arnsten, A. F. T., & Shanafelt, T. (2021). Physician Distress and Burnout: The Neurobiological Perspective. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 96(3), 763–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.12.027 ↩︎

- Beyond Blue: National Mental Heath Survey of Doctors and Medical Students 2013, accessed 12th March, 2024: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://medicine.uq.edu.au/files/42088/Beyondblue%20Doctors%20Mental%20health.pdf ↩︎

- Neff K. D. (2023). Self-Compassion: Theory, Method, Research, and Intervention. Annual review of psychology, 74, 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047 ↩︎